To discuss India’s recent military history and the challenges of crucial decision-making, Frontline spoke to General N.C. Vij, who served as the Chief of Army Staff from December 2002 to January 2005 and as Director General of Military Operations during the 1999 Kargil conflict. In his book, Alone in the Ring: Decision Making in Critical Times, General Vij offers an insider’s account of pivotal episodes in national security. Edited excerpts:

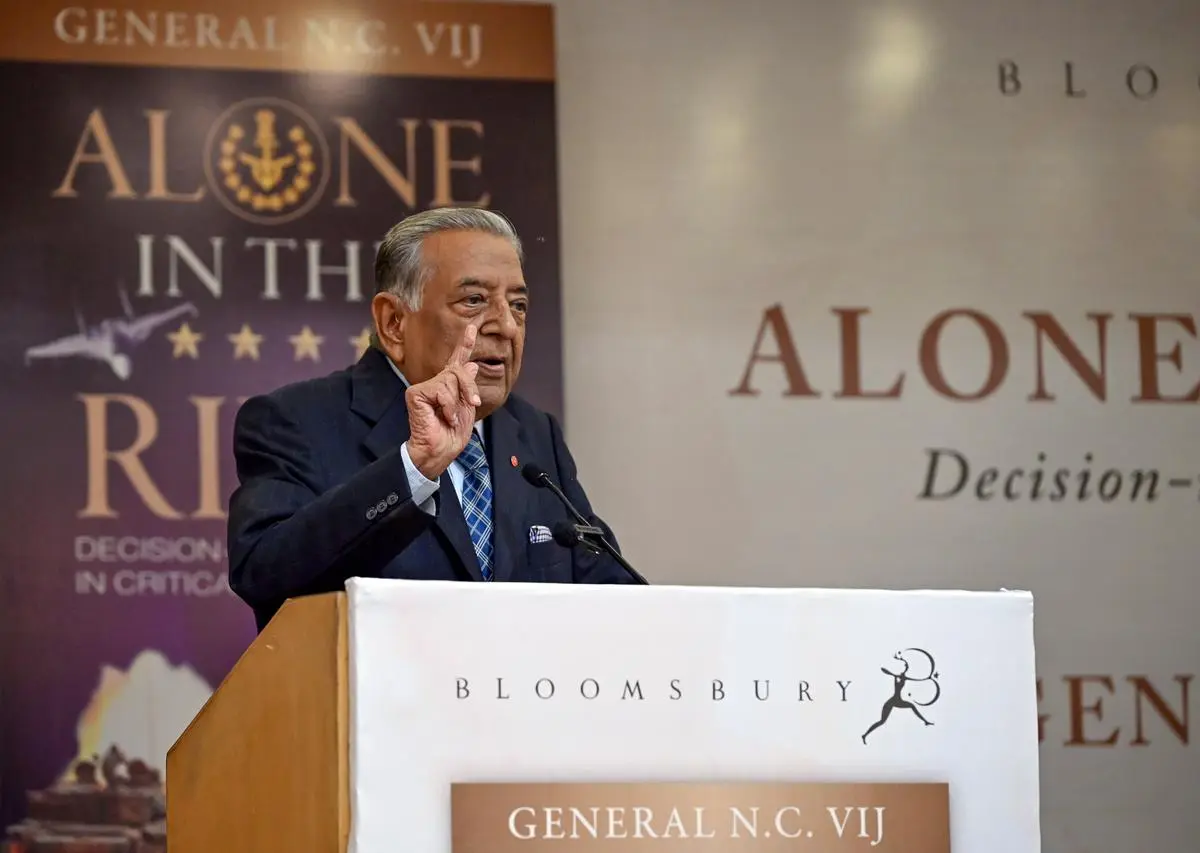

General (Retd.) N. C. Vij addresses the gathering during the book launch event of Alone in the Ring: Decision-Making in Critical Times, at Kamala Devi Complex in New Delhi on May 15, 2025.

| Photo Credit:

Jitender Gupta/ANI

You mention early on in your book that India reacted with more restraint than necessary during Kargil and did not allow military operations across the Line of Control. That won us friends internationally, but 26 years later, how do you balance this restraint with the isolation Pakistan suffered?

These are two different times—1999 and now. That time we had just done the nuclear experiment and India wanted to look a very responsible part of the world. I’m telling you only the government’s thinking. Not that the army was with that kind of decision. Wars are fought by the government, not by the armies alone. Armies are instrument of war.

Secondly, the government didn’t want to do anything where perhaps the world thought that India is not a responsible power. And thirdly, they had perhaps somewhere lurking at the back of their mind a fear of nuclear response from Pakistan.

As far as today’s scenario is concerned, it’s entirely different. The government has made up its mind that Pakistanis are using the nuclear threat as an instrument of spreading terrorism. So, they’ve said, okay, strategic restraint, but controlled escalation. We’ll go up the ladder to controlled escalation. The moment we hit the terror camps, we announced very clearly that we have only gone after the terrorism camps, but the escalation was done by Pakistan, not by us.

India won many friends during Kargil with its policy of restraint. So, possibly restraint can cut two ways—create problems for military operations, but win friends internationally. How do you look at this?

A lot of time has gone by—26 years. The media has changed so much: that everything you do, the moment you do it, is reported. So, we had to make sure that we have a very good narrative because now any war that is being fought has two parts. One is the strategic aspect, which is the war fighting, and second is the story building, the narrative. The narrative has become a very major issue today.

Perhaps our narrative somewhere in between, we slackened off. So there was a requirement to wake up for that, and our delegations went. When you saw the response of the world, everybody was sympathetic but kept it quite muted and said you should finish this war, there’s a nuclear problem, we must have restraint. These are lectures that don’t help us. We want to convey to the world that we are suffering from terrorism at the hands of Pakistanis. Terrorism is also a threat to the world, which Americans must know well. They suffered in 9/11 and fought in Afghanistan for any number of years.

A soldier looks at a drone at the Akhnoor sector near the Line of Control (LoC) in the Jammu region on May 19.

| Photo Credit:

AFP

Since you saw both Kargil and Operation Sindoor, what are the main changes from Operation Vijay to Operation Sindoor?

A lot of changes. That day, the government gave us orders not to cross the Line of Control. We were asked to take Kargil only and not go elsewhere. Given an option, we perhaps wouldn’t have gone to the Kargil area. We would have gone to many other areas in the PoK, which would have been far easier to pluck and perhaps then come to Kargil later.

Was this proposal made to the government by you?

Yes. Everything was discussed behind the door. They felt that our case will be stronger if we take Kargil. Those who have been to those areas will see that these hills are absolutely straight up and there are no approaches. Very difficult objectives.

But this time the government gave us free hand. Every time we have upgraded the response. We did a surgical strike just a few kilometers across the Line of Control. After that, Balakot happened. We have now multiplied that by nine times and gone straight for terrorist targets not only in PoK but in the heart of Punjab. We have used aircraft. First time, we did it only with foot troops. So we have upgraded our response.

Also Read | India and Pakistan are still very much on the razor’s edge: Ramanathan Kumar

Would you say air power, unmanned aerial vehicles, drones are the instruments of modern warfare, like in Ukraine?

Yes, these are very much instruments of the future and will be used heavily. But that does not reduce the importance of the Army and Navy. Our Navy was in a very good position to take on Karachi. They didn’t do it because there was no requirement.

All three services will remain important. But yes, drones and stand-off weapons are major additions. Some people use the terminology of “no contact” war. Well, I am infantry and I don’t believe in that. It’s no contact at the initial stage. But ultimately, if you have to fight, contact is inevitable. There will be ultimately army on the ground because only then you can capture areas.

All these conflicts took place under the nuclear umbrella. How much rationality should we give to the other side that they will not use the ultimate option?

Pakistanis have not changed their nuclear threshold. But their Director General, Lieutenant General Khalid Kidwai, who was advisor to the National Command Authority, has mentioned four things. One is territorial integrity—any part of their country lost will be a problem. Second, destruction of their forces—if you destroy their main strike forces, that will be a problem. Third, if you destabilise that country politically. Fourth, if you economically strangle them.

So these four are very well stated. There is a threshold, but you can operate below that threshold. That’s what we did. We had started the Cold Start doctrine. We said we’ll make shallow incursions so that we remain below their nuclear threshold.

India has put the Indus Waters Treaty in abeyance. Pakistan’s Joint Chiefs chairman said this constitutes existential threat. Is this a nuclear trigger?

Pakistan has always considered India as an existential threat. That has been their approach all along. As far as the Indian armed forces are concerned, from my younger days, we were told that a stable Pakistan is in our interest. But Pakistan has always felt they are under an existential threat.

Water is definitely a threat. I’m glad that for the first time after discussing for many years, Indus Water Treaty needs to be changed. It was drawn 60 years back under different circumstances. The population profile has changed, our requirements have changed. The Prime Minister has put it on the table and said we will do it. We are open to discussion, but it has to be resolved. They don’t listen. So somewhere you have to change the rules.

During the first days of Operation Sindoor, Pakistanis claimed they downed our jets. Reuters also claimed three jets came down. But our Air Marshal took days to confirm losses. Did this delay give Pakistan propaganda advantage?

There are two aspects. Firstly, losses are part of any operation. You can’t fight a war without losses. We also did it under certain conditions and restraint. Perhaps we didn’t want to suppress their air defense, which we should have done.

Yes, perhaps we should have mentioned it on day one. But during war, you are not discussing your losses. During the Kargil War, during the operation, we were not mentioning losses either. You were talking of bodies coming back to Delhi through proper channels.

In Alone in the Ring: Decision Making in Critical Times, General Vij offers an insider’s account of pivotal episodes in national security.

| Photo Credit:

By Special Arrangement

But during Kargil, we lost two MiG aircraft, and Squadron Leader Ajay Ahuja was killed, and Flight Lieutenant Kambampati Nachiketa was captured. Doesn’t it serve purpose to be upfront?

Then I will tend to agree with you that on the first day itself, perhaps we could have done it. It would have served our purpose better. When the Air Marshal spoke, he made it very clear that all pilots are safe. So obviously, the unspoken part was that some aircraft have been lost. Perhaps we could have mentioned number of aircraft.

Pakistanis have also not mentioned their losses. They have also lost aircraft, which they have not mentioned. [Ed Note: This has not been verified yet by any source.] But our side has started talking about it.

When MiGs came down in Kargil, was there pressure on armed forces to hit back that day?

At that time, the aircraft came down. First, we used helicopters, an easy target. Then we were flying at low heights. The Air Force changed their tactics. Not crossing the Line of Control to remain within conditionality. They started going beyond 20,000 feet, where missiles couldn’t reach. We also had got guided munitions.

Pressure was there. Loss of aircraft and helicopters was not welcome news and had demoralising effect at that point. But that was only for a couple of days. After that, the Air Force changed tactics and flew 550 sorties with no loss. So operation was great success.

You mentioned in 2004 an effort to resolve a dispute with Pakistan about coordinated withdrawal from Siachen Glacier, and you quote Prime Minister Manmohan Singh telling you, “General, you’re being very hawkish.” What was the context?

After the Congress government came to power, they held a meeting in our military operations room. The government was considering pulling back troops a little on both sides to reduce tension. Our point was that if you pull back, say five kilometres on our side and five kilometres on the Pakistan side, there’s a world of difference. For us to get back to those five kilometres may take more than day. Pakistanis will be there in an hour or two.

We said Pakistanis cannot be trusted. We had experienced them enough to understand that whatever they say is a pack of lies and they will do what they want to do. We suggested to the Prime Minister that we should not do that. Siachen is far too important. We don’t want to risk Siachen, and it’s very difficult to recapture any part of Siachen once occupied.

We gave two reasons. One, even when Prime Minister Vajpayee was in Lahore in February ‘99, Pakistanis were already intruding into Kargil. The Lahore Declaration was being signed, and that is the audacity with which they operate. Number two, infiltration was still taking place. We were having 3,000 odd terrorists inside the Valley and Jammu. Infiltration cannot take place unless Pakistan army is actively supporting it.

When I told this to Dr Manmohan Singh, he said, “You are being very hawkish.” Coming from Dr. Manmohan Singh, who was so polite and soft spoken, it was many degrees more than that. We said, “Sir, we are professionals. It is our duty to tell you the truth without mincing any words so that there is no lack of understanding as to what we are playing with.”

Did he take your advice?

He said, “Where can we discuss this further? We want to discuss amongst ourselves.” I took him to the DGMO’s [Director General of Military Operations] office. They sat for half an hour, came back and said, “We have thought over it. We’ll drop the idea.” He very much took the suggestion we had given.

Here is a very important point. Between the government and the Armed Forces, there must be a very good professional rapport. It is duty of the Armed Forces to tell them the absolute truth without mincing any words. And it is the job of the government to listen to that professional advice very seriously. What they decide ultimately is their choice. But this rapport and understanding must exist.

Also Read | Operation Sindoor blurred the lines between security and showbiz

In Iraq, there were pressures from Americans for India to deploy troops. You make interesting points that our troops would have been mercenaries, Americans were looking for cheap soldiers, and there was no UN sanction. You wrote letters to political leadership saying this was bad idea. Did your letters swing the decision?

We were told by the government. The Secretary of Defense made two visits to India. We had meetings in the Defence Minister’s office. The point was, firstly, we were operationally very heavily occupied. We were building a fence that was 740 km long. We had no time. Number two, we had experience in Sri Lanka, where we felt that operating in somebody else’s country is a different ball game altogether. Number three issue was why should we fight under anybody else’s flag, where we have no control, we are only instruments to be used.

I wrote to the Prime Minister and the Defence Minister before the CCS meeting. The strategic community was very strongly in favour of sending troops to Iraq. They had their reasons. One, India will increase its influence in the world. Two, an opportunity to get into the Security Council. Three, [US President George] Bush had told [Lal Krishna] Advani he will tell General Musharraf to lay off Kashmir. But we stuck to our issues and mentioned we should not go. After the CCS meeting where we all gave our views, the Prime Minister said only one word—chintan karenge—and the meeting broke up. After month and half, decision was taken that no troops will be sent.

I cannot say for sure whether it was our recommendation that swung the issue, but I’m sure they would have given credence to it. We did our duty. We told them what we felt was right and stuck to it. We have dealt with the Pakistanis at length. We must learn one thing that you cannot trust them.

Amit Baruah was The Hindu’s Islamabad-based Pakistan correspondent from 1997 to 2000. He is the author of Dateline Islamabad.